How did music happen? Part 3: “The Mafa and the Octave”

This is part of a series of articles. Click here to go back to Part 2: “Spartans, Chimps & Neurons”

Nature VS Nurture

A question we inevitably ask ourselves is whether music is something we are born with or something we learn to understand and appreciate with time. The answer is probably both but things are not as simple as they may seem. It’s time to tackle the millennia-old opposition of ‘Nature VS Nurture’.

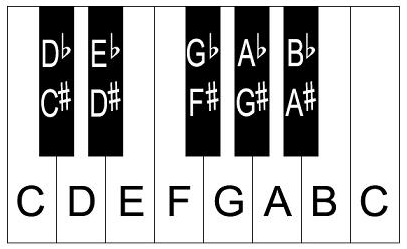

As ‘nurture’ generally means ‘culture’ in our context, the first logical thing to do is look at different human cultures and compare their musical affinity and tastes. Obviously, different parts of the world have very different kinds of music but in terms of structure, the similarities are evident. In practice, a difference in musical tradition usually means different variations of the same basic principles. While it would be risky to call certain musical figures ‘universal’ there are some which come as close to the definition as possible. Of course, I’m talking about the octave – the interval between one musical pitch and another with half or double its frequency. It seems to have penetrated the musical traditions of cultures which have never had anything in common and have had no opportunities to exchange information in any way. The octave is just… natural. It’s the result of our brain incorporating the physical principles of the world it lives in into the way it decodes information.

And while an octave is somewhat universally valid, other intervals are not as widely implemented and accepted. They vary in popularity in different parts of the world and their meaning changes with time. To give an example, a major seventh chord is something we’re generally used to and can easily like but it would have been considered disharmonious by Beethoven. This applies to scales as well. In different geographical regions, the number and position of pitches within an octave can vary. Music from the Middle East can sound very sad to a westerner because it’s mostly minor but, as you can imagine, it’s not necessarily sad.

Despite the obvious role of culture in the human perception of music, there are certain traits we definitely inherited and didn’t learn over time. This has been proven by the Cameroon experiment.

The Cameroon Experiment

In the far north of Cameroon, in small villages in the Mandara mountains, live the Mafa people. They are one of the most culturally isolated people on the planet. Their settlements often suffer a total lack of electricity. Aside from being sad and nice at the same time, this also means many of the Mafa have never been exposed to any kind of western cultural influence. No movies, no art and most importantly – no music. The Mafa, however, have a musical tradition of their own, mostly manifested during ceremonies. They have flutes of different sizes and they control the pitch by manipulating the small holes at the tips of the instruments.

Researcher Tom Fritz with members of the Mafa tribe

A few years ago a team of scientific researchers interested in the topic of music ‘universals’, led by Thomas Fritz, went to Cameroon and conducted a very simple but very productive experiment. They played western melodies to the Mafa and asked them how each piece made them feel. Even the locals who had never experienced this type of music before were able to distinguish the ‘sad’ tunes from the ‘happy’ and the ‘scary’ ones, at a rate significantly higher than chance. The same excerpts from Western music were later played to German listeners and the results were similar.

The Mafa being subjected to Western musical stimuli

If the opposite had been done and Mafa music had been played to westerners, the results wouldn’t have been informative, as, traditionally, the Mafa don’t really associate any emotions with their music. In many tribal languages around the world a word for ‘music’ doesn’t even exist so it is often represented by the word for ‘movement’ because it’s usually closely connected to dancing. Even so, the Cameroon experiment demonstrates that no matter where we came from and what cultural influences we’ve been subjected to, somewhere inside our brains there’s something we all share that helps us understand emotions music was meant to evoke.