Scientists scan Sting’s brain. Because they can.

Ever wonder what goes on inside the mind of a musical genius? Well, cognitive psychologist Daniel Levitin was lucky enough to be able to peek inside the head of Sting and see what exactly happens when the world-renowned singer, songwriter, and composer does what he does best – music.

How does one get permission to “enter” the skull of a superstar? Easy – under the right circumstances, you just ask. Sting just happened to be in Montreal for a concert and decided to pay a visit to McGill University. To be fair, we may have created the impression that Levitin should have been seriously starstruck by the encounter. While this may be partially true – come on, it’s Sting we’re talking about – the cognitive psychologist has seen his good share of celebrities of the music breed. Levitin has done extensive research and published numerous texts, took part in films, documentaries, events and interviews particularly on the subject of music and its relation with the human brain. Throughout the years many big names you know from show business have collaborated in these projects and have exchanged knowledge and experience with Levitin and his team. So it’s probably safe to say Sting had good reasons to visit the scientist, curiosity, and respect undoubtedly among them.

How does one get permission to “enter” the skull of a superstar? Easy – under the right circumstances, you just ask. Sting just happened to be in Montreal for a concert and decided to pay a visit to McGill University. To be fair, we may have created the impression that Levitin should have been seriously starstruck by the encounter. While this may be partially true – come on, it’s Sting we’re talking about – the cognitive psychologist has seen his good share of celebrities of the music breed. Levitin has done extensive research and published numerous texts, took part in films, documentaries, events and interviews particularly on the subject of music and its relation with the human brain. Throughout the years many big names you know from show business have collaborated in these projects and have exchanged knowledge and experience with Levitin and his team. So it’s probably safe to say Sting had good reasons to visit the scientist, curiosity, and respect undoubtedly among them.

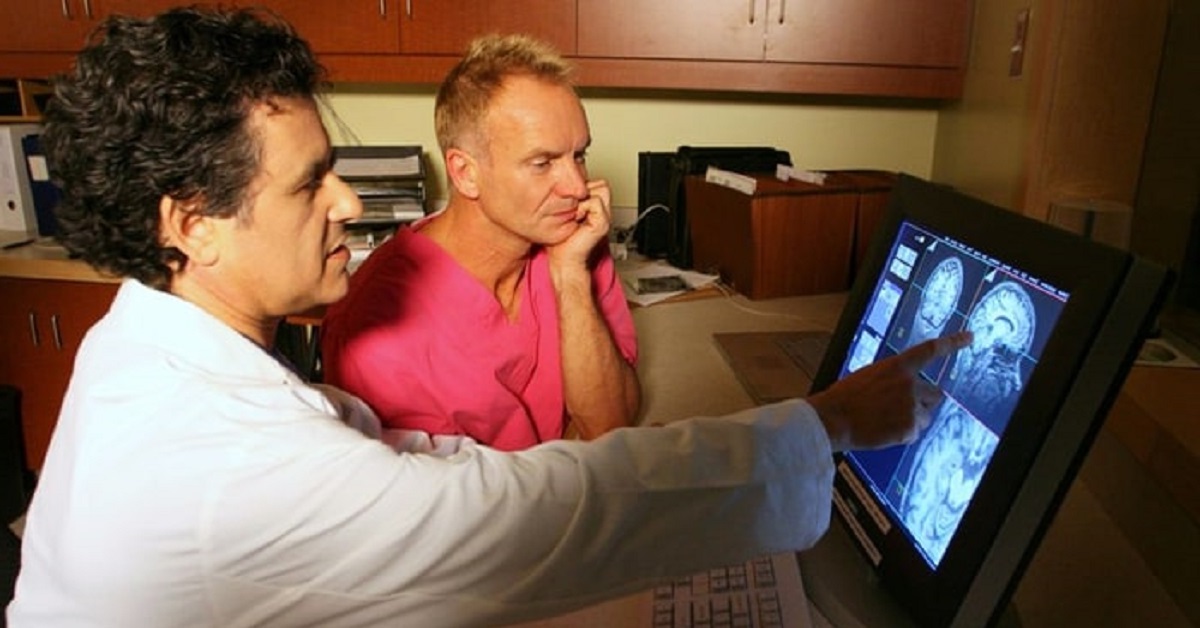

So Sting asked for a tour. If you’re a scientist and Sting asks for a tour of your lab, you say yes and, of course, ask to scan his brain. As a result of the star encounter, Levitin and his colleague Scott Grafton (of the University of California, Santa Barbara) have published their analysis of the fMRI images they made of the musician’s brain.

“State-of the-art techniques really allowed us to make maps of how Sting’s brain organizes music,” Levitin said. The team saw that composing awakened brain regions distinct from those used in writing or other creative work. However, Sting used similar brain areas while listening to and imagining music. The scientists also observed the patterns of activity in Sting’s brain as he listened to various songs to see how similar he found them and what that meant in terms of brain signals.

Unlike the scientists, Sting perceived songs such as his “Moon Over Bourbon Street” and Booker T. & The M.G.’s “Green Onions” as related. As it happens, they share the same key and tempo. In future, the scientists believe this technique could be used to show how musicians, writers and other artists find unexpected links between various ideas.

Unlike the scientists, Sting perceived songs such as his “Moon Over Bourbon Street” and Booker T. & The M.G.’s “Green Onions” as related. As it happens, they share the same key and tempo. In future, the scientists believe this technique could be used to show how musicians, writers and other artists find unexpected links between various ideas.

Functional brain imaging has revealed much about the neuroanatomical substrates of higher cognition, including music, language, learning, and memory. The technique lends itself to studying of groups of individuals. In contrast, the nature of expert performance is typically studied through the examination of exceptional individuals using behavioral case studies and retrospective biography. Here, the scientists combined fMRI and the study of an individual who is a world-class expert musician and composer in order to better understand the neural underpinnings of his music perception and cognition – in particular, his mental representations for music. They used – get ready for some new grammar – state of the art, multivoxel pattern analysis (MVPA) and representational dissimilarity analysis (RDA) in a fixed set of brain regions to test three exploratory hypotheses with Sting.

What the team has found was that composing recruited neutral structures that are both unique and distinguishable from other creative acts, such as composing prose or visual art. Also, that listening and imagining music recruited similar neural regions, indicating that musical memory shares anatomical substrates with music listening. In addition, the MVPA and RDA results helped them to map the representational space for music, revealing which musical pieces and genres are perceived to be similar to the musician’s mental models for music. Overall, the scientists’ hypotheses were confirmed.

The act of composing, and even of imagining elements of the composed piece separately, such as melody and rhythm, activated a similar cluster of brain regions and were distinct from prose and visual art. Listened and imagined music showed high similarity, and in addition, notable similarity/dissimilarity patterns emerged among the various pieces used as stimuli: Muzak and Top 100/Pop songs were far from all other musical styles in Mahalanobis distance (Euclidean representational space – sorry, I know it’s complicated), whereas jazz, R&B, tango, and rock were comparatively close. Closer inspection revealed principled explanations for the similarity clusters found, based on key, tempo, motif, and orchestration.

Fun times for Levitin and his team. If you still haven’t decided to quit your education and become a stripper, make sure to head over to Drooble first, where you can find tons of awesome music-loving people and more music-related facts 🙂